Key Takeaways

- Tariffs, export controls and investment restrictions have turned the US-China economic relationship into a primary arena of strategic competition, with sanctions and controls accelerating the fracture of once‑benign global supply chains along political lines.

- Trade is deepening within aligned blocs and weakening across rival blocs, creating new opportunities for connector economies like Vietnam that sit between great‑power camps and act as intermediaries.

- Australia remains embedded in US-led security networks while staying economically tied to China, exposing firms to sanction risks and resource nationalism.

Free trade. It’s an idea that has underpinned the global economy for centuries and, for most of recent history, has enjoyed a certain degree of consensus: Trade between nations lifts incomes, improves efficiency, encourages specialisation and allows countries to share not just goods, but knowledge. For businesses and households alike, it’s a hallowed concept and one that has left Australia materially better off. So why does this centuries‑old ideal suddenly feel under threat?

The principle is simple: Countries specialise in what they do best. But recent events suggest that economic logic is no longer the only force shaping trade. The United States’ incursion into Venezuela, following years of sanctions and diplomatic pressure, points to something more overt, with a clear interest in the country’s crude oil reserves. Washington’s overtures to acquire Greenland, backed by threats of new tariffs on European allies that oppose the deal, make trade measures look less like routine policy and more like leverage in geopolitical bargaining. Progressively, the invisible hand is transforming into a fist when strategic resources are at stake.

States still pursue their economic ties with a clear eye to self‑interest. What’s changing is the toolkit. Economic instruments are increasingly used to draw political lines, fragment markets and redirect investment. For a trade‑exposed economy like Australia, this shift reaches directly into boardrooms and shop floors. As political rivalries reshape globalisation, businesses are being forced to rethink where they source, whom they sell to and how exposed they are to decisions made far beyond their borders.

Is the world fragmented on political lines?

Globalisation’s technocratic promise – to remove barriers, deepen integration and let markets work – has fractured into a strategic contest. The most consequential fault line runs through the US-China relationship, where tariffs, technology export controls and investment restrictions have turned trade into a primary arena of rivalry rather than a neutral conduit for efficiency.

What once looked like benign interdependence now resembles weaponised connectivity.

Economic tools like sanctions, tariffs and export controls have shifted from background policy levers to front‑line instruments of state power, with one major index recording a 446% increase in global sanctions designations since 2017. As the United States and China use their economic weight to secure strategic advantage and reshape patterns of trade and investment, Australia finds that familiar commercial ties can rapidly become geopolitical fault lines. In response, Canberra has tightened investment screening and critical‑infrastructure rules in parallel with security partners, signalling that security concerns now sit alongside, and sometimes above, market-first logic.

The most unmistakable evidence that this logic now shapes crisis response came after the start of the Russia‑Ukraine conflict in February 2022. Sweeping sanctions and energy embargoes imposed by the United States, the European Union and their aligned partners forced a rapid reconfiguration of oil and gas flows, with Russia redirecting its exports to Asia. Europe scrambled to find alternative suppliers at higher costs. Australia stood firmly with the Western bloc, joining sanctions and accepting higher energy price volatility as the price of political alignment. Long‑running US‑led sanctions on Iranian and Venezuelan oil, and now US military action in Venezuela, underline that when strategic resources are at stake, economic pressure can be backed by hard power.

Between a bloc and a hard place

These shocks have coincided with a measurable shift in how and where countries trade. Recent research tracking bilateral trade flows has found that trade within aligned blocs is growing faster than trade between them. Bilateral trade between the United States and China has grown around 30% less than their trade with the rest of the world since tensions escalated in 2018, reflecting a broader trend of trade reorienting along geopolitical lines. The pattern is most pronounced in energy, high-technology goods and some intermediate products, where security concerns are the highest. While global trade volumes remain substantial, and many supply chains still span rival capitals, political alignment is playing a larger role in determining who trades with whom and on what terms.

Australia sits within the US‑aligned security and sanctions bloc, yet remains heavily economically intertwined with China, which continues to dominate its export profile. Despite a bruising period of trade restrictions, China still received 32.2% of Australia’s exports in 2023-24. When allies deploy more complex tools, from sanctions to interventions, against countries that are important to Australia’s trade, Canberra is compelled to balance strategic loyalty against concentrated economic exposure. For Australian businesses, this means that exposure to geopolitical risk increasingly depends not just on where suppliers are located, but on how governments classify those relationships. With fragmentation increasing the material and political costs of trade between blocs, carefully considering how to approach market diversification is emerging as central to risk management strategy.

Connector economies

Even if globalisation hasn't declined in a material sense, there’s little doubt that investment patterns have shifted. Greater geopolitical distance is associated with a decline in cross-border transactions across all categories, with pullbacks particularly pronounced when it comes to foreign direct investment (FDI) between blocs. Cross-bloc FDI is falling about 12 to 20 percentage points more than trade and investment flows between countries that are politically aligned.

Here is where connector economies come into play. As trade and investment increasingly follow geopolitical lines, this group of non‑aligned or loosely aligned countries is finding space to act as ideological and logistical intermediaries between rival blocs. They attract capital precisely because they sit between major powers, offering access, capacity and a degree of political insulation rather than a strong alignment with either side.

What are the characteristics of connector economies?

The appeal of connector economies rests on several recurring characteristics that make them attractive to investors looking to de‑risk their exposure to geopolitical tensions:

- The capacity for low‑cost manufacturing.

- Preferential or indirect access to major markets through trade agreements or customs unions.

- Geographic, cultural or political proximity to at least one major power.

- Extensive use of special economic zones (SEZ) that combine lighter regulation and tax incentives, providing fast and predictable set-ups for cross-border projects.

Countries like Vietnam and Thailand illustrate how these features can overlap. Both offer low‑cost manufacturing and sit in China’s backyard, which supports strong inflows of Chinese FDI. By contrast, when the focus is on indirect access to large Western markets and SEZ-based platforms, attention shifts towards places like the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, Mexico and parts of Central and Eastern Europe, where trade agreements and zone regimes can be combined to offer investors market access and mitigate political risk.

What does this mean for Australia?

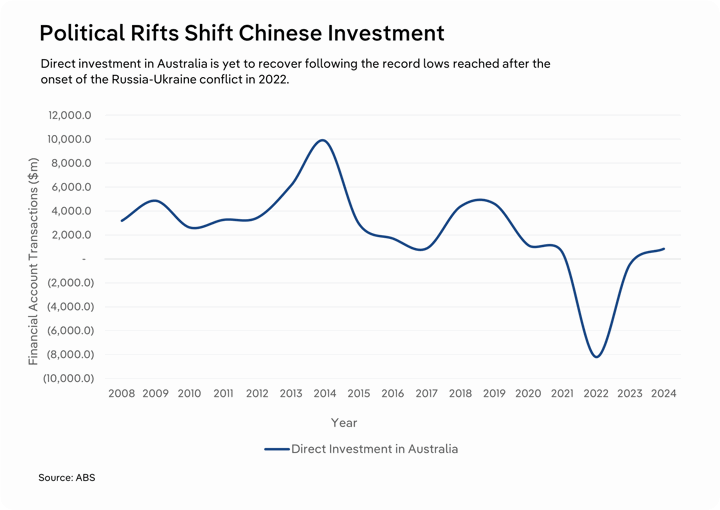

China’s role as an investor in Australia has undergone a significant shift over the past five years. Chinese investment in Australia plummeted 32% in 2023 alone, dropping to its second-lowest level since 2006, with 2024 registering as the third-lowest year since 2006. China is redirecting much of its outward investment towards South-East Asian markets and Belt and Road economies, many of which act as connector countries between rival blocs.

This shift is not just about economics. It reflects Australia’s growing role in US‑aligned bloc politics, alongside China’s own strategic pivot towards green energy, technology and markets seen as more politically reliable. Fewer capital inflows from China could continue to strain Australia's infrastructure development.

China and Venezuela

For more than twenty years, Venezuela has sat at the heart of China’s strategy in Latin America. Nicolas Maduro even described Xi Jinping as ‘an older brother’ and most of Venezuela’s oil exports are destined for China. This kind of highly politicised, bilateral dependence is the opposite of what investors and firms are seeking as geopolitical risk rises. Connector economies, by contrast, offer diversified access to multiple markets and a degree of political insulation, which is precisely why trade and investment are being rerouted through them as bloc tensions deepen. For Australian businesses, the lesson is not to double down on a single politically exposed route, but to use connector economies to build alternative supply chains and market entry points that are less likely to be disrupted when great powers clash.

The costs of fragmentation

The idea that political choices govern where our goods go and how we get them is, for most people, largely invisible in everyday life. Yet the costs of fragmentation have the potential to tangibly reshape economic and social dynamics.

The economic disruptions from fragmentation are already large enough that the International Monetary Fund now projects world trade volume growth to drop from 4.1% in 2025 to 2.6% in 2026. Some estimates suggest that, in a severe fragmentation scenario, the long‑run loss in global GDP could reach up to around 5%, with overall costs exceeding those seen during the 2008 global financial crisis or the COVID‑19 pandemic.

When tariffs and sanctions reconfigure supply chains away from comparative advantage, resources are pushed into less efficient uses and production structures become more convoluted. If fragmentation persists and protectionism spreads into tighter capital controls, lower migration and weaker international cooperation, living standards will worsen over time. This will be especially challenging for the emerging markets that dominate much of Australia’s export profile.

Political rivalries have intensified investment screening, with a growing share of FDI now subject to national‑security reviews rather than purely economic tests. If production networks become more regionally and politically clustered, Australia risks missing out on the diversification benefits of more globally spread supply chains.

Where does Australia sit in a fragmented economic landscape?

A hinge, not a hostage

Today’s fragmentation is far less hemispheric than in the past. The global economy is breaking into a more complex and fluid set of alignments.

Australia is a resource‑rich hinge in the jigsaw of economic development, plugged into US‑led security networks while relying heavily on Chinese demand for its commodities. Complete alignment with either the United States or China would contradict core interests. Leaning too far towards Washington risks loosening critical ties with Beijing, while diluting the alliance would undermine security foundations.

Public opinion reflects this uneasy straddle. Lowy Institute polling shows trust in China has eroded, while trust in the United States fell by about 20 percentage points in 2025. Even so, the US alliance is seen as the more fundamental strategic partnership, even though more than half of Australians expect China to become the more powerful country in the years ahead.

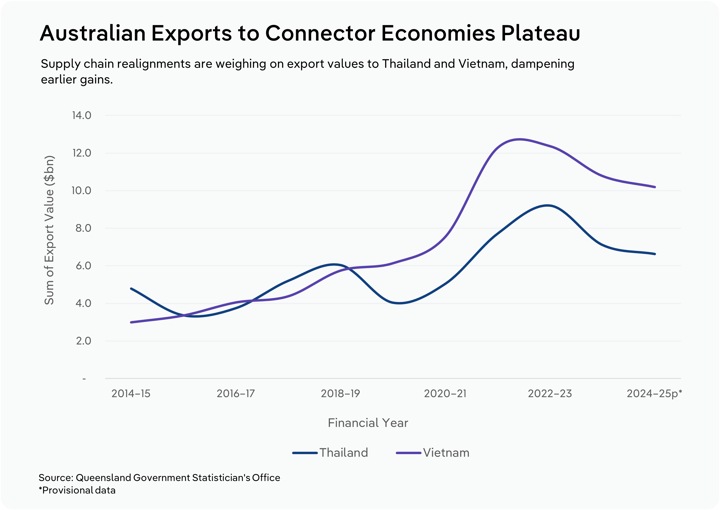

Australia has spent the past decade deepening its ties with connector economies like Thailand, Vietnam and Mexico. Still, those relationships have started to lose momentum since the Russia‑Ukraine war upended global investment flows, making it harder to treat these markets as simple substitutes for China or the United States.

The new petro-politics

Much of the conflict in recent decades has been fought over resources, especially oil. There has also been a broad understanding that war is costly and that simply seizing resources is a blunt, inefficient way to secure them.

What is emerging now looks less like old‑fashioned grabs and more like resource nationalism. For Australia, this matters because the resources in play are no longer just barrels of crude oil but minerals, like lithium, that are essential in clean energy technologies and electric vehicles. Australia holds some of the world's largest deposits of battery-grade lithium, making it a key player in the energy transition.

China has already been shifting more of its lithium investment and offtake towards South American producers, which gives Beijing alternatives to Australian supply. However, with Washington's increasing influence in the South American region, geoeconomic motives could once again shift supply chain currents.

This newer form of resource nationalism is more subtle than armed conflict but no less strategic. It plays out through investment screening, long‑term offtake agreements and industrial policy. For Australia, the challenge is to leverage critical minerals as an asset without turning them into a point of vulnerability or a tool that others can easily weaponise.

Final Word

The weave of global politics is no longer background noise for Australian businesses. In a moment when it feels like the ‘weeks where decades happen’ are piling up, staying anchored in the logic of current events while keeping a long‑term lens will be essential.

Political rivalry and geoeconomic tools like tariffs and sanctions are starting to redraw supply chains, shift demand and move prices in ways that show up directly in contracts, jobs and household budgets.

If economic protectionism congeals into rival camps, some of the gains from decades of integration will inevitably be unwound. But Australian businesses aren't condemned to passivity. By drawing on a globally connected workforce, deepening ties with connector economies and treating geopolitics as a core business constraint rather than an afterthought, Australia can resist being neatly filed into a single box, even as rivalries strain global networks.

In a world where allegiances are fluid and trade flows are increasingly political, the ability to shift course rather than stand still is the real source of advantage.